Below is a full Report of CNN unveiling the harm and the contamination of Chromium-6 in the drinking water of more than 200 Million Americans.

By Susan Scutti, CNN

Updated 7:27 PM ET, Wed September 21, 2016

“(CNN) Dangerous levels of chromium-6 are contaminating tap water consumed by hundreds of millions of Americans, according to a national report released Tuesday.

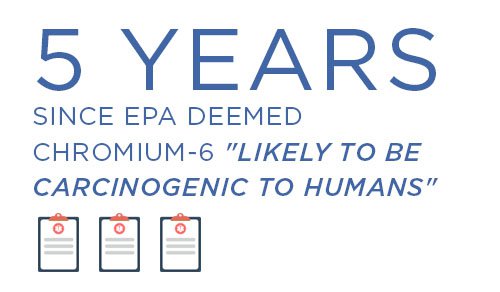

Chromium-6 is the carcinogenic chemical that was featured in the popular 2000 movie “Erin Brockovich,” starring Julia Roberts as the titular activist. The US Environmental Protection Agency has never set a specific limit for chromium-6 in drinking water.

There is scientific uncertainty regarding safe levels of this chemical in drinking water and possible long-term consequences of ingestion. But this new analysis from the Environmental Working Group, an independent advocacy group, examines evidence from water systems throughout the nation and concludes that the tap water of 218 million Americans contains levels of chromium-6 that the group considers dangerous.

“Whether it is chromium-6, PFOA or lead, the public is looking down the barrel of a serious water crisis across the country that has been building for decades,” Brockovich said in a written statement Tuesday, blaming it on “corruption, complacency and utter incompetence.”

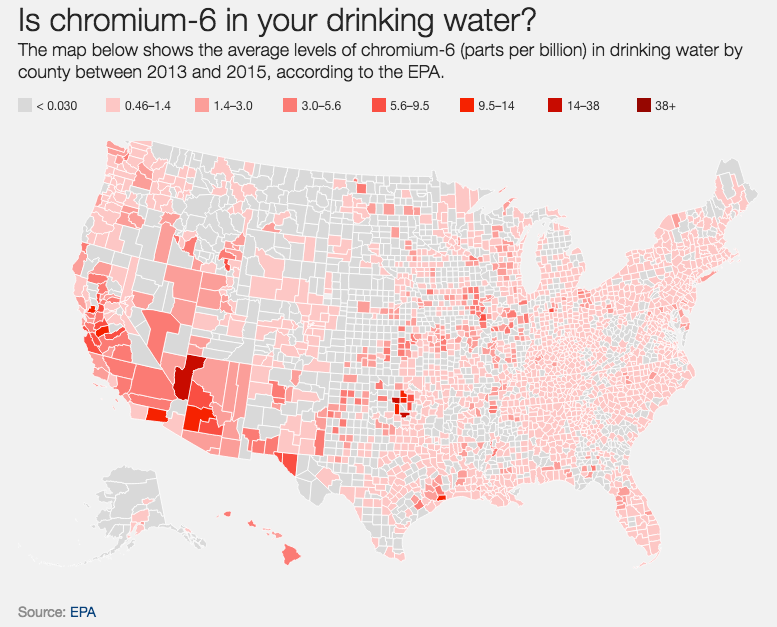

Specifically, the new report indicates that levels of chromium-6 are at or above 0.03 parts per billion in 75% of the samples tested by local water utilities on behalf of the EPA between 2013 and 2015. Seven million Americans receive tap water with levels of chromium-6 that are higher than the legal limit established by California — 10 ppb — which is the only state to enforce a maximum contaminant level. All these figures may be confusing, but the real point is that chromium-6 is one of many chemicals in our environment, said Bill Walker, co-author of the report and managing editor of the Environmental Working Group. The group receives grant money from the Turner Foundation, which is chaired by CNN founder Ted Turner, who is no longer involved with the news organization or any Turner entity.

“Americans are exposed to dozens if not hundreds of other cancer-causing chemicals every day in their drinking water, their consumer products and their foods,” Walker said. “And what the best science of the last decade tells us is that these chemicals acting in combination with each other can be more dangerous than exposure to a single chemical.”

What is chromium-6?

Chromium is a naturally occurring element found in rocks, animals, plants, soil and volcanic dust and gases, according to the National Toxicology Program.

It comes in several forms, including what is commonly called chromium-3, an essential nutrient for the body. Chromium-6, which is rare in nature, is produced by industrial processes. Chromium-6 is used in electroplating, stainless steel production, leather tanning, textile manufacturing and wood preservation, according to the National Toxicology Program. Chromium-6 is also found in the ash from coal-burning power plants and used to lower the temperature of water in the cooling towers of power plants.

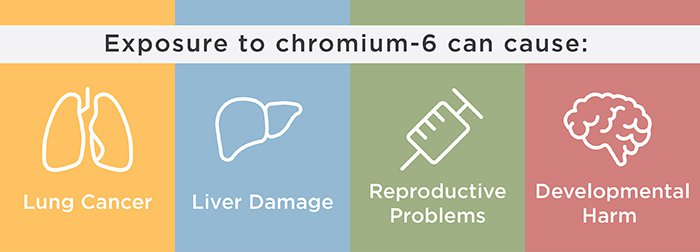

Scientific reports have indicated that breathing in airborne chromium-6 particles can cause lung cancer. Based on these reports, the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration sets strict limits for airborne chromium-6 in the workplace.

By contrast, although it lacks a specific limit for chromium-6, the EPA has established a drinking water standard of 100 parts per billion for all forms of chromium. This limit was established in 1991 based on scientific information at that time indicating that large quantities of chromium were toxic.

In 2008, a two-year study by the National Toxicology Program found that drinking water with chromium-6 caused cancer in laboratory rats and mice.

“In terms of cancer studies, that is the gold standard of animal studies,” said David Andrews, co-author of the report and a senior scientist with the Environmental Working Group. He said a separate scientific study found a higher incidence of stomach cancers in workers routinely exposed to chromium-6.

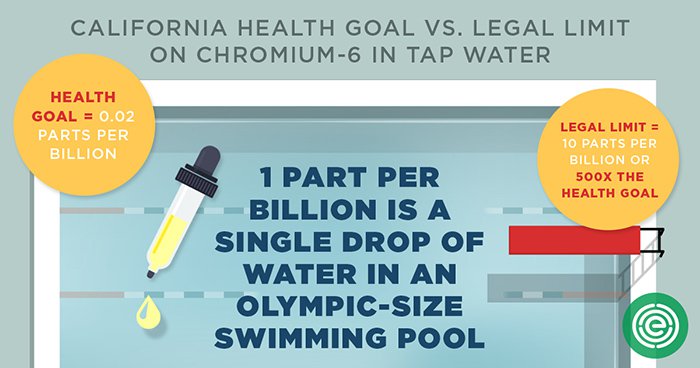

Based on the 2008 report and other research, scientists at the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment set a public health goal of 0.02 parts per billion in tap water. The new report notes that the scientists believe this level would pose only “negligible risk over a lifetime of consumption.”

Still, Walker and Andrews say this is a problem. Exposure to very low levels at crucial periods during the development of a fetus, infant or child could cause “much more serious problems” than it does for an adult drinking a larger dose, Walker explained.

In 2014, California regulators adopted a legal limit of 10 ppb as the state’s enforceable standard: 500 times higher than the public health goal established by scientists. New Jersey and North Carolina government scientists independently assessed a health-based maximum contamination level for chromium-6 that is only slightly higher than California’s.

Unregulated contaminants

For its report, the Environmental Working Group reviewed the EPA’s third Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule.

“The EPA periodically does this: goes down and looks for what it calls unregulated contaminants,” or chemicals in drinking water that are not regulated, Walker said. The EPA gathers its information through local utilities and then takes the results “under advisement,” according to Walker.

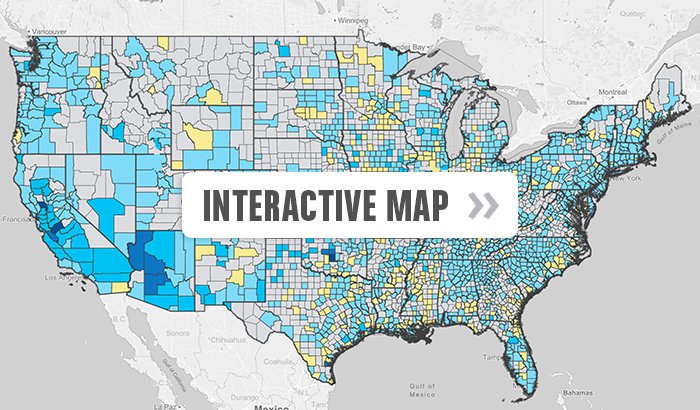

According to the group, the report indicated that only one public water system had total chromium exceeding EPA standards, but 2% of the water systems — 1,370 counties — had chromium-6 levels exceeding California’s standard of 10 ppb.

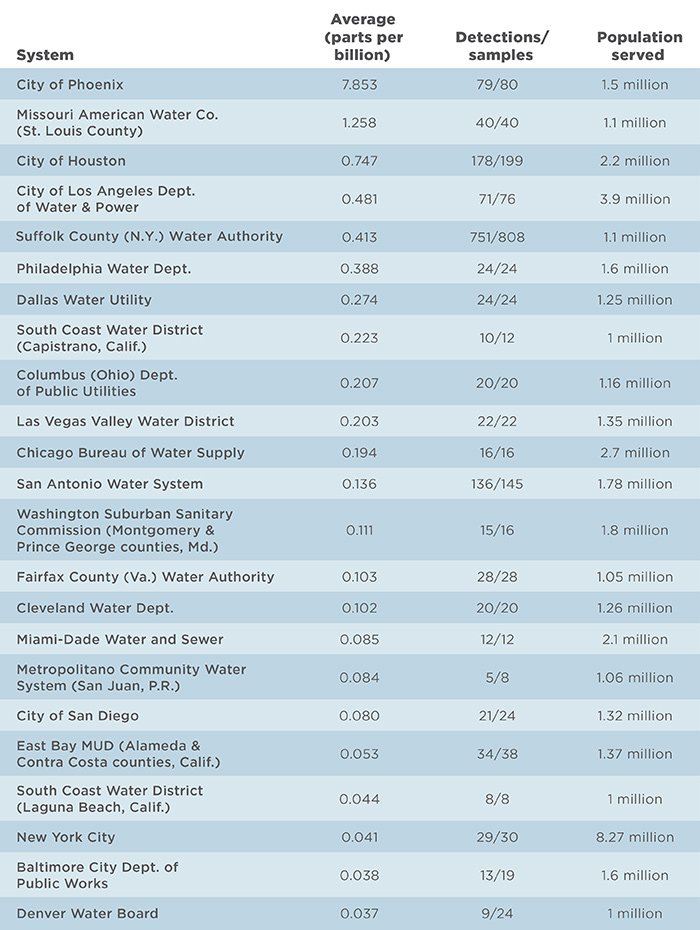

Oklahoma, Arizona and California had the highest average statewide levels and the greatest shares of detections above California’s public health goal of 0.02 ppb, the report found. Of major cities, Phoenix had the highest average level at almost 400 times this health goal. St. Louis County, Houston, Los Angeles and Suffolk County, New York, also had relatively high levels.

“EWG’s report is another wakeup call that we must take this issue seriously,” said New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, a member of the Environment and Public Works Committee, who this month introduced an amendment to require testing of all public water supplies for unregulated contaminants.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality said in a statement that it weighed all of the scientific evidence and “does not anticipate excess cancer risks from chromium-6 concentrations routinely measured in drinking water in Texas.”

The EPA did not directly address the report, but a representative said the agency is working on a health assessment of chromium-6 that will be released for public comment in 2017.

“When you find widespread evidence of contamination, do something about it. Don’t just study it to death,” Walker said, adding that the new report is not about “trying to raise the alarm about a single chemical. We’re kind of using chromium-6 as a poster child for systemic failures of drinking water regulation.”

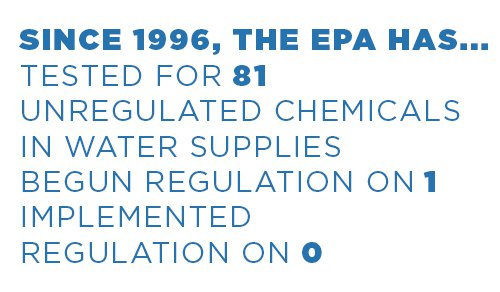

The standoff is the latest round in a tug-of-war between scientists and advocates who want regulations based strictly on the chemical’s health hazards and industry, political and economic interests who want more relaxed rules based on the cost and feasibility of cleanup. If the industry challenge prevails, it will also extend the Environmental Protection Agency’s record, since the 1996 landmark amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act, of failing to use its authority to set a national tap water safety standard for any previously unregulated chemical.

The standoff is the latest round in a tug-of-war between scientists and advocates who want regulations based strictly on the chemical’s health hazards and industry, political and economic interests who want more relaxed rules based on the cost and feasibility of cleanup. If the industry challenge prevails, it will also extend the Environmental Protection Agency’s record, since the 1996 landmark amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act, of failing to use its authority to set a national tap water safety standard for any previously unregulated chemical.